Travels with Waldmire

This is a reprint of an article written for the Illinois Times dated July 23-29, 1998. This periodical was sent to the Oklahoma Route 66 Association by the Waldmire family. The Oklahoma Route 66 Association is the proud caretaker of a U-Haul truck that Bob painted a few years before his death; today it sits near the Pedestrian Underpass in Chelsea, OK.

BY TOM TEAGUE

Itinerant artist, eco-vegetarian, and retired Route 66 icon Bob Waldmire is coming home to Cardinal Hill

Bob Waldmire, the Springfield native who became Route 66's most prominent gypsy, is leaving the road. Fans and visitors to his Old Route 66 Visitor Center in Hackberry, Arizona, may see this as a departure. But for Bob it's a return a return to work, family, and his pre-celebrity solitude.

Bob's father, Ed, invented the corn dog in Amarillo, Texas, toward the end of World War II. In 1949, he opened the Cozy Dog Drive In in Springfield. Later he became the city's first human rights commissioner. For all this, he was inducted into Illinois' Route 66 Hall of Fame in 1991.

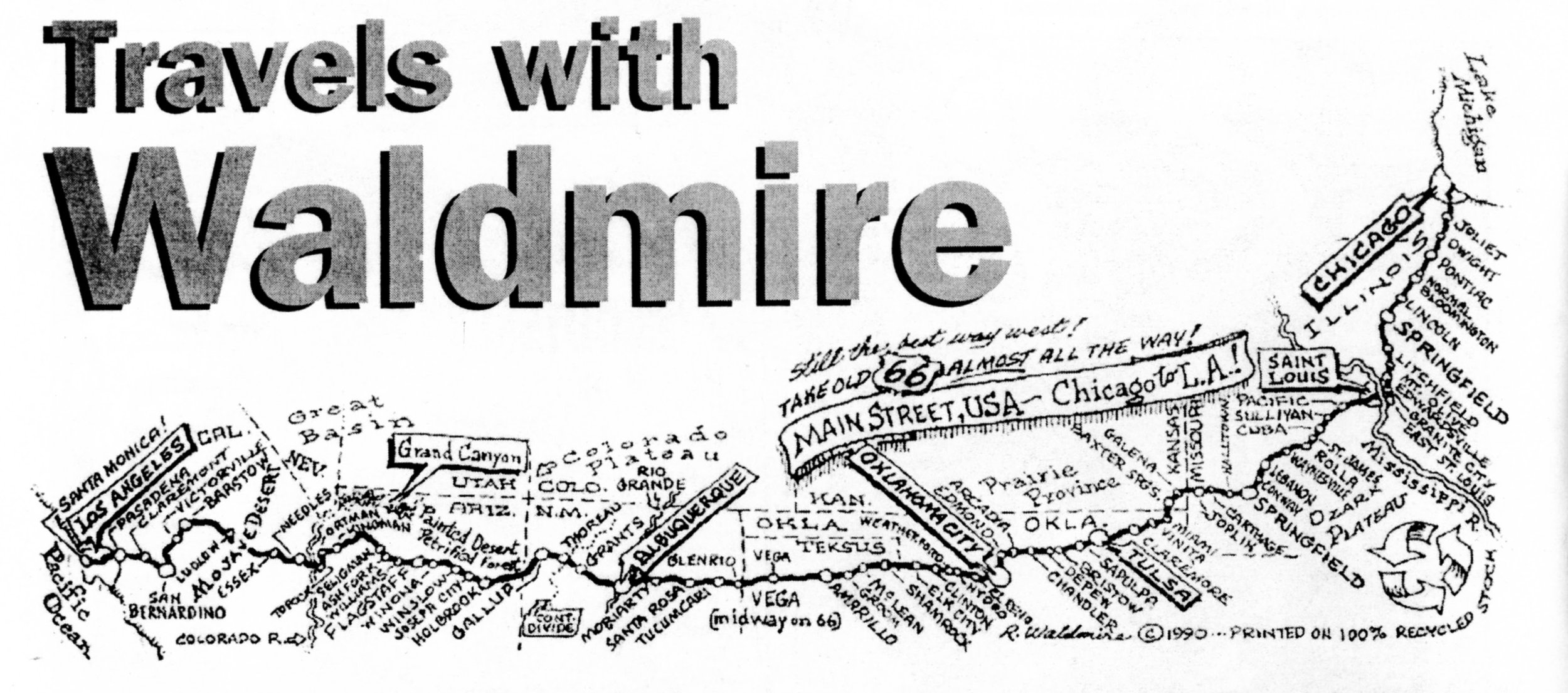

Son Bob first gained individual Mother Road recognition in 1992 when he published his bird's-eye view map of the highway. The ten-page atlas and six-page legend established him as one of 66's keenest observers. A year and a half later when he opened his center, he graduated to icon status. Now he's setting that aside to commute between the Chiricahua Mountains and the Illinois prairie.

It's a life few others would choose or even imagine. But it's the one Bob needs to lead. Just a shade too old to be a Baby Boomer, he has a lot of irons he still wants to pull out of life's fire. Only by moving on does he feel he can get this done.

In the odyssey that's become his career, Bob has seen our nation's grandest scenic vistas. His first encounters with wild nature, though, took place within the city limits of Springfield.

"We lived two miles north of the Cozy Dog on South Sixth Street," he said. "A couple of blocks from us, there was a vacant lot. I would go over there, usually by myself, and poke around under the cardboard and tin, looking for little snakes, spiders, and other critters. At home, Mom would allow me to keep them in the back yard in boxes."

In 1956, Ed Waldmire bought a farm near Rochester and named it Cardinal Hill. Along the farm's river-bottom land, Bob's exploring continued.

"It was so ominous and intimidating in the woods that I wouldn't go down there at first without a friend," he said. "It was like a jungle. I built a tree house along the river, but it was a long time before I was bold enough to spend the night there by myself."

Knowledge eventually overcame fear and Bob spent a good part of his teen years studying the bottomland and other wild areas. Now he can let a black widow spider crawl across his hand to prove the creature's gentle nature.

"I took a different path in my childhood," he said, "not just from my brothers, but from my fellow humans. It's not that I was antisocial or didn't participate or date all through school. But I had this other interest that nobody else had."

After high school, this interest led Bob to a summer course at the University of Arizona in Tempe.

"We'd been to Arizona the year before on a family trip and I'd loved it," he said. "The desert bug had bit me. I had a dorm room at school, but spent most nights out on the backroads looking for and catching whatever was out there: snakes, tarantulas, scorpions. Back in the dorm, my roommate was mortified by them."

Bob dropped out of Tempe before long and came home. Here he enrolled at Springfield Junior College (now SCI). He enjoyed his botany and biology courses. With slicked back hair and a button-down collar, he even ran for student office. But he still flunked out. Then he tried Southern Illinois University in Carbondale intermittently during the late Sixties. Finally, there was only one place left to go.

"All of us kids grew up in the Cozy Dog," Bob said. "Whenever one of us needed money, Dad would make a place for us. I worked there off and on through my mid-twenties."

It was during these stints at the Cozy Dog that Bob discovered, then developed his artistic skills.

"I started when I was in high school by lettering menus," he said. "I found it gratifying to have my work seen. Later I painted billboards and other signs. My first ones were crude and amateurish, but Dad was not concerned about the level of competency. I have a good eye and a steady hand and in time I became quite good."

Around 1971, Bob also became a vegetarian and a hippie, qualities that he maintains to this day. This caused troubles at work, where he was already getting restless.

"The wastage of food at the Cozy Dog became offensive to me," he said. "I'd clean off the tables and trays, but instead of throwing the food away, I'd set it aside. Then I'd feed it to the farm dogs at Cardinal Hill. Or I'd scatter it along the back roads for the foxes and raccoons."

While still in high school, Bob had ridden a bus alone to Mississippi to visit his mother's half-brother. "It was the first time I'd been away from home by myself and I loved it," he said. "I loved the smell of diesel, the bus depots. Red Bud, Illinois-what an exotic place!" A wanderlust that he'll probably never satisfy was born. As discomfort at the Cozy Dog grew, it would kick in again.

"When I was in in college at Carbondale, I'd seen a bird's-eye poster of the town," he said. "That gave me the idea to do my own of Springfield. Then I did two black light posters. One was a single-color design and the other was a multi-color Mandela spiral. "Dad sold 500 of the Springfield poster one time to a country kitchen chain for fifty cents apiece. I was just as angry as can be. I said I didn't want to be selling tens of thousands of posters at a low price. This was my art. It had taken me all summer to draw. It was almost insulting to sell it for that amount.

"Dad's idea was the more value we sold, the better. Finally he just threw up his hands and said, 'All right, I won't sell any more' and walked away." As for Bob, he made plans to peddle his posters from his '65 Mustang 2+2 fastback.

"I had a girlfriend then," he said. "I've always said that was the only time I was really in love, but I don't think I really was. The fork in the road came when she wanted to settle down. What I wanted to do was travel, sell my artwork, and meet new women. So I sacrificed the choice I had at home and hit the road as a loner."

As a fulltime wanderer, Bob would look for a town that appealed to him. Usually it had a college. He'd spend a month or more there, getting to know the people and the owning sights. Then he'd draw a panoramic, bird's eye view poster of the town. Often it would be sponsored by the businesses it featured. Then he was off to another town and another map – thirty-four in all. Along the way, he also drew dozens of wildlife sketches and nature scenes.

Bob used all those years behind the wheel or a pen to hone his philosophy of life. Though it's as complex and detailed as one of his posters, he summarizes it easily in his soft, measured drawl: "Small is beautiful. Slow is beautiful. Old is beautiful." No person or thing should be any bigger than necessary. Hurrying places only cheapens the moment. And nothing is as old as nature itself, yet so new every day.

After about a year on the road, Bob decided that his Mustang was both too small and too sporty for his new self-image. On a trip home, he traded it in on a Volkswagen squareback. For thirteen years, the VW was not only his car it was also his home. In 1985, he retired the squareback to a shed at Cardinal Hill and bought the vehicle he's most commonly linked with: a Volkswagen camper van. With Route 66 shields and maps painted on it, it soon became an easily recognizable sight in Springfield and on the road.

About four years later, he bought and converted an old school bus. In 1994, he bought a flatbed truck to help haul his possessions out to Arizona. And just this past May, he soothed his long-term regret over selling his Mustang 2+2 by buying another one.

"I've always babied my vehicles and related to them as a kind of companion and shell," Bob said. "You get intimately attached to a vehicle if you have it long enough. It's a joy simply to be in it. You don't even have to be traveling. Just to turn a key and fire up an engine when you're in one spot and engage the gear and start to move...there's nothing like it."

The irony of an environmental advocate so many motor vehicles is not lost on Bob.

"I deal with a lot of guilt," he said. "But I love older vehicles. I can't really justify consuming the fossil fuels and polluting the environment and killing myriads of small creatures. But I've had to do it to propel my livelihood and distribute my artwork. And in that artwork. I try to sensitize the viewer and reader to nature. So I drive as little as possible and I go at sub-lethal speeds when I can. If you're trying not to kill butterflies, that means under twenty miles an hour."

It was while traveling at such sub-lethal speeds that Bob took his ten-year turn down Route 66.

"I was on my way back to Illinois from Arizona on 66," he said. "And I was discouraged when I came to a dead end and had to get on the interstate. Back on 66, there was this bump-ba-bump-ba-bump as I drove over the poured concrete slabs - a feeling of being closer to the land and nature. Within a few miles, the light bulb lit that I should make a map about the road."

Bob started his new project as soon as he returned to Cardinal Hill. A hundred thousand pen strokes later, he was done. A careful reader with a magnifying glass could actually use the map to travel 66. But it wouldn't be easy because Bob refuses to be read in a linear manner. The road somehow makes it from one side of a page to the other. But it has to snake its way through a forest of sketches and thumbnails. The people of the road are there, the businesses, the plant and animal life, the geology, the climate practically everything Bob had ever wanted to talk about.

"Initially, I thought I'd knock out a four-page map in a few months' time," he said. "It ended up taking sixteen pages and four years. When I started it, I was a young middle-aged man. When I finished, I was an old middle-aged man. It aged me."

Published in 1992, the map also determined the course of Bob's life for at least the next six years.

He'd long dreamed about returning to the Chiricahuas and settling down. But the camaraderie of Route 66 and its commercial potential intrigued him. Soon he started dreaming of heading west and establishing an "international, bioregional Route 66 visitor center." After his map came out, he combined a land search with his marketing trips. When a friend sent him a news clip about an abandoned gas station in Hackberry, Arizona, Bob included that site on his itinerary.

"Traffic was very light when I stopped there," he said. "It was in the fall. Nice weather. I walked around the gas station and up the hill. Wheels started turning. I thought, "What a trip to actually get this! It's too good to be true. I left a card in the door with Mom and Dad's phone number. The owner called in a couple of days and we got together.

"He was a little leery of me at first, with the van and the beard, but he was real interested in selling. He named his price-no dickering. I called Mom. I could hear Dad from his easy chair saying, 'Buy it! Buy it!’"

Although he was in the later stages of a losing bout with colon cancer, Ed Waldmire led a delegation of ten family members to Hackberry in February to close the deal. In deference to Bob's fear of flying, they took Amtrak.

"Everywhere I look, I see work," Ed told his son. But they closed the deal. Bob made arrangements to have the gasoline storage tanks removed and the family returned home.

Ed Waldmire had always wanted to publish a book of writings by his philosophical heroes. It would include "Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven," by Mark Twain; “The Age of Reason,” by Thomas Paine; Thomas Jefferson's Bible; and Dwight Eisenhower's farewell address. When it was clear his father wouldn't be able to do the book himself, Bob promised to finish and print it for him.

"We'd always butted heads and had to avoid certain subjects to get along." Bob said. "But there was time to make peace toward the end and we all made a lot of peace. When I promised to finish his book, Dad could no longer speak very well. But I can remember him holding my hand in both of his in response."

In October 1993, two months after his father's death, Bob put his van on a trailer, hitched it to a Ryder truck, and drove to Hackberry. Except for trips home to visit his mother, he hoped to spend the rest of his life there.

After a cold and lonely winter, Bob's dream started taking shape. In the depressions where the gas pumps used to be, he planted a cactus garden. On the south side of the main building, he built a solar greenhouse. Out back on his twenty-plus acres, he marked and annotated a nature trail. And to catch the eye of travelers from the east, he installed the rusted-out hulk of a '39 Plymouth near his Joshua tree.

Inside, Bob displayed his life's collection of natural artifacts and cultural memorabilia. Tables and racks held his postcards, maps, and posters. One corner held his father's book collection, now called the Edwin Waldmire Memorial Peace Library. In another corner, visitors could enjoy a cup of fresh coffee at an original Cozy Dog booth or snack on sterile hemp seeds roasted in a solar oven. Here and there were aquaria holding rattlesnakes or other temporary guests. On a road already famous for its idiosyncratic charm, the visitor center quickly stood out.

All self-marketed artists by necessity lead a schizophrenic life. First, they must have solitude to concentrate and let creativity have its way. Then they have to go out and sell the product. Through word of mouth and steady media coverage, Bob was as commercially successful at Hackberry as he'd ever been. But after two years, he decided that wasn't what he'd been looking for.

"It's been great fun to play host and proprietor," he said. "I'm good at it. But the numbers, the overwhelming numbers, really surprised me. A hundred visitors a day is common. If I'm in a good mood and not depressed, it's great because you fill a need. People are asking questions because they really want to know. But when they come in with video cameras and want to do their own interviews, they can be annoying.”

"I also underestimated the volume of non- 66, commuter, or commercial traffic. I became angry and tense and just resentful of how many people were going back and forth. And I was stuck right there beside the traffic to look out the door of the visitor center and see it or hear it or smell it."

Since 1996, Bob has been planning how to leave Hackberry. A neighbor's decision last fall to quarry decorative boulders on adjacent land only cemented his decision. The visitor center is on the market. An October 19 concert there by a touring band of middle-aged British rockers will mark its last day of business. After that, it's Ryder Truck time again.

This latest move surprised Jim Dodds, Bob's best friend since grade school.

"I thought he'd found his utopia in Hackberry," Dodds said. "I'm disappointed he's selling the place. I tried to reason with him, but Bob is a total innocent in so many ways. He can't be happy unless he's unhappy."

Which is one way to drive an artist. Bob has an option on forty acres in his beloved Chiricahuas. He hopes someday to exhaust his wanderlust there-on foot. But his bonds to his mother and his promise to his father are drawing him back to Cardinal Hill first.

"My mom, Virginia, has always been the woman I cared about most," he said. "She is the best hope I have of completing the most important project in my life: my father's book."

Like his Route 66 map before it and the Cozy Dog business itself, this project has already grown beyond expectations. Besides the anthology,itI now will feature oral histories, reminiscences from Ed's friends and family, photographs, and dozens of Bob's own drawings. He'll park his bus at Cardinal Hill and work from there.

"It will dwarf the 66 project," Bob promised. So it is not with regret, but anticipation that he takes leave of a legend he helped build. He's even rubbed the Route 66 shields off the doors of his van. "It felt good to be an icon," he said. "But it will feel better to be an ex-icon."